My response to Kai Stinchcombe

The anniversary article reflecting on Ten Years of Bitcoin triggered a storm of heated debates. And no wonder–it was a great write-up launched at the best possible time—the calm silence before Christmas, when no one is working and everyone has plenty of time to lazily wander around the house and wonder, with a craving for juicy news.

Kai makes a number of excellent arguments, but he seems to be knocking at the window while missing the wide open door.

Let’s start with the basics...The “Ten Years” Argument

It’s common knowledge that Bitcoin was first released at the end of 2009 (version 0.1). A number of bugs were discovered and resolved between 2009 and 2013. Looking at the issues that were addressed back then (transaction malleability, unexpected network fork, etc.), it is hard to associate the word “stable” with it at any time before early to mid 2014, even with the caveats and disclaimers one often uses to handwave road bumps with any new technology. For all practical purposes, the age of Bitcoin as an applicable, functional technology rather than an abstract concept is less than three to four years old.

By all practical measures, three to four years means a technology is still in its infancy. ARPANET, the precursor to the Internet, was established as early as in 1983, but it took seven to ten years before we saw the explosive growth of the 90s. That being said, someone in 1994 could have written a perfectly logical article titled “Ten years later, no one’s come up with a use for the Internet,” for example.

It took another ten years for fundamental changes in travel, stock trading and a number of other industries to take place. In fact, the overwhelming shift to online shopping over brick and mortar didn’t happen until 2010 or later.

Social media and the online advertising industry that it facilitated didn’t hit their stride until the mid-2000s. After that it took another 10 years for online advertisement to finally wrest control from TV and print, only really occurring in the last year or two. All in all, it took 20 years or so for Internet to deliver on its promises. Why would be Bitcoin or any other manifestation of blockchain be any different?

Disruption of existing industries: payments, stocks, banking, distributed storage…

If history offers any lessons, the disruption of an existing industry does not happen simply as a result of the invention of new technology. New business models, fueled by the technology or creative applications in the context of existing models, are instead often the cause of a disruption to the paradigm. It’s not that unusual for existing players to embrace and prosper with new inventions rather than allowing themselves to become obsolete.

We still buy cars from dealers—but the majority of car shopping happens online. Did dealers go out of business? Not quite. The smarter ones embraced “the online” to drive even more sales than before.

Stock trading — today many investors trade using online brokerage accounts. Charles Schwab saw lots of early success as a pioneer in online trading. Did any broker go out of business as stock trading shifted to the internet? I’m sure some did. Did others survive and become even stronger—that’s not even a question.

Bitcoin and blockchain are no different than other technology innovations we’ve seen before. In fact, history is repeating itself right in front of our eyes.

Nasdaq and a few others united behind R3—the consortium looking to enable trading on the blockchain. The hope is to simplify the stock settlement across market participants—a manual, involved process that takes up to three days to complete after the purchase. Yes, you read that right—it takes around three days for your one-click purchase to finally settle and register in all affected books. Could the blockchain provide a superior alternative? It’s easy to see that it should be explored, at least.

Visa and MasterCard operate a global network of connected and mutually trusted nodes. Lots of work goes into certification, audit, and secure operation of individual nodes. Could blockchain ease some of the requirements as a result of its trustless model? Absolutely! Is it possible that payment costs will be lower as a result? No doubt. Does it mean the world of plastic cards must switch to the blockchain for each and every payment? Absolutely not!

There is no need to consider extremes—no need to aim for the extinction of a business or a vertical for blockchain to succeed. There are plenty of opportunities to compliment, enhance, and extend.

Where are the opportunities?

Joe—the cool guy—launched a file storage service and offers it cheaper than S3. Would you trust him with your sensitive files? Not likely. What if the payment for Joe’s service was cryptographically contingent on your retrieval of files and matching of hash codes? We just replaced the trust to the unknown party Joe with trust in the integrity of a decentralized network, supported by hundreds of billions in individual investments that is unlikely to go away anytime soon. Clearly, there is an opportunity for Joe and his customers.

Joe launches a Kickstarter campaign on a new, cool IOT device. The campaign goes well, devices are shipped, Joe maintains a server with device registration. Suddenly Joe goes out of business, taking the servers with him and rendering the devices useless. Would it be better if the registration data was stored in a blockchain, eliminating the risk of owning a device that outlived the manufacturer?

More on this point—the number of accounts and registration records is exploding with the growth of the consumer and industrial IOT. Account maintenance is becoming a serious expenditure, affecting margins and profitability. At the same time, it is almost never a core business function for an IOT maker, who would happily hand it over elsewhere. Clever developers at Xage (https://xage.com/) have already deployed an account management solution for industrial IOT (Disclaimer: I am not involved with Xage in any form or fashion).

Despite the hysteria surrounding the Experian story, anyone with meaningful experience in corporate IT would say that Experian is not any worse than the average. In fact, not better or worse, just average. The issue is not that they should have been better. It is rather the enormous concentration of data creating unbearable risks.

In absence of better alternatives, Experian must be the collector of records and the custodian, compute FICO and perform a number of other functions that leads to enormous risk concentration. An alternative that stores records on the chain and only infrequently opens access to Experian and other parties based on explicit customer authorization could be much more secure and reliable, leading to a clear win-win. Notice that credit ratings did not go away, credit agencies did not get replaced with the blockchain, but rather agencies became a participant in a new engagement model.

I could go on for hours, but hopefully the overall premise is clear by now:

- Bitcoin and blockchain should not be evaluated in the context of head-to-head competition looking to drive incumbents into obsolescence.

- Similar to the Internet and other innovations, Bitcoin and blockchain will take time to mature.

Technologies do not change the world, business models do.

Utility Coin Valuation

Cryptocurrency valuation has been a hot topic since the earliest days of Bitcoin, and has only become more controversial with the introduction of tokens and ICO (Initial Coin Offerings). Some investors see ICOs and the resulting tokens as potential Ponzi schemes in the making, though others believe ICOs herald a new era in Venture Capital. So which is it?

As always, the truth is somewhere in between.

In my view, the controversy is largely due to a lack of agreed upon coin valuation models. These would be standards which consider specific factors of a coin offering and enable an easy, apples-to-apples comparison, untarnished by one’s emotions or beliefs. The primary challenge is that such models and methods have yet to be developed, an issue which will certainly be addressed as the coin economy matures.

In the meantime, I’ve tried to compile a model of my own. This is my attempt at coin valuation based on fundamentals. Consider it more of a brain dump than anything formal or extensively researched.

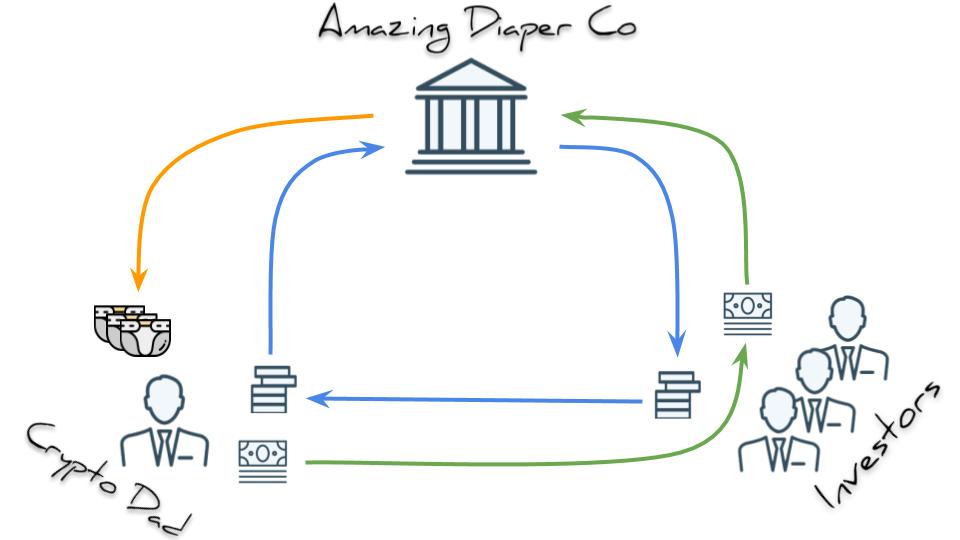

Let’s say that you’re invited to take part in an ICO by Amazing Diapers, a company which plans to offer premium diapers at 1 ADC (Amazing Diaper Coin) per pack. A pack of equivalent Pampers diapers is sold for \$30 USD. Does that mean that 1 ADC has a potential value of \$30 USD?

If 1 ADC entitles the owner to receive one pack of Amazing Diapers and equivalent diapers are sold for $30 USD, then you might think that’s obviously the value of the coin. The reality is a bit more complicated. Let’s consider that for a minute.

$$Coins\ in\ circulation * Coin\ value = { Unit\ Value * Volume\ Sold }.$$

\(Unit Value * Volume\ Sold\) represents the total economic value of all coin transactions. When more transactions occur, the demand for a coin increases, driving up the value of all coins equally.

The formula can be rewritten to derive the value of single coin:

$$Coin Value = { Unit Value * Volume Sold \over Coins\ in\ circulation}.$$

Intuitively, this represents the idea of coin price equilibrium, a situation driven by the scarcity of ADC coins and the demand for Amazing Diapers. The more coins that are in circulation, the lower the price will be. At the same time, the more diapers that are sold (and the more ADC denominated transactions that take place), the more valuable the coins will be.

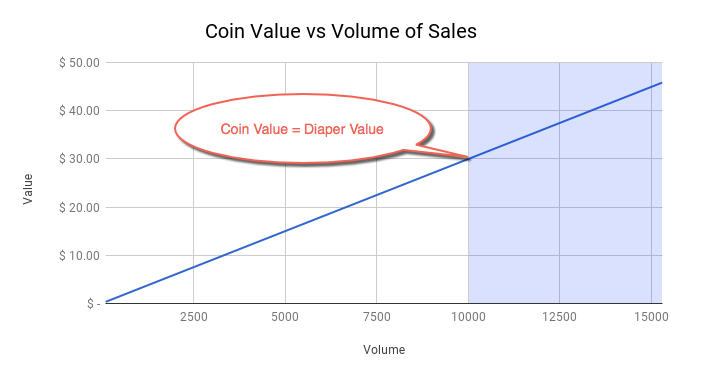

The relationship between volume and the coin’s value is linear, as you can see in the graph above. For the sake of the argument, we assume a 15% growth rate across arbitrary time intervals, but we could have picked any other growth rate we liked as the value is not relevant to our discussion. Irrespective of the growth rate, the coin value eventually approaches the perceived value of a pack of diapers—in our example, that’s $30 USD.

Let’s unpack this a bit more. Potential customers of the Amazing Diaper company need to obtain 1 ADC per pack. How likely are they to pay more than \$30/ADC if the perceived value (or market value) is \$30? Not very likely.

So what happens then?

There are a few possibilities:

- Sales volume drops (i.e. prospective Amazing Diaper customers switch to another brand of diapers)

- The issuer starts offering more Amazing Diapers per coin. This is akin to the process of deflation, or appreciation of a coin’s value.

- The coin issuer released more coins into the market. Depending on the volume of newly released coins, the coin may inflate (experience a drop in value) or stay the same.

The first option is not very interesting—in essence the system reaches a point of equilibrium, with the coin value capped at the value of the underlying good. The growth stops, capped by the equation \(Coins\ in\ circulation * Unit\ value\).

For continued growth, the issuer needs to enact one of the two remaining options: deflate the coin or issue more coins. It is remarkable that in either case the issuer begins to act as a monetary authority—the spitting image of the Federal Reserve—with all the associated power and responsibility.

The deflationary path leads to appreciation of the coin’s value. Indeed, one could now buy more diapers with a single coin, raising the value as potential diaper buyers will be willing to pay more for the coin. ICO investors and coin holders are clearly the beneficiaries of this scenario.

But in the final scenario—coin inflation—the issuer is the only beneficiary, leaving investors to twist in the fiscal winds.

Of course, releasing more coins into circulation obviously benefits the releasing party. Coins are sold to market participants for a profit, which is collected by the seller—in our case, that’s the coin issuer. Notice that ICO investors who held their coins see no benefit here and, in fact, may suffer if the coin’s value drops as a result of the additional supply.

An important takeaway from this discussion is the need for sound monetary policy management in order to achieve and sustain steady growth. If a one-time issuance of coins is not followed by active engagement with the resulting market on the part of the issuer, the coin’s growth potential is restricted.

Another takeaway, perhaps the most important of all, is that the success of the coin shifts the leverage away from investors to a coin’s issuers. Initially, when the transaction volume is small relative to the number of coins held by investors, there is little the issuer can do. However, the coins aren’t valuable yet either.

As time goes by and transaction volume grows, driving up the coin value, the issuer gains more and more control over the distribution of the wealth between themselves and their investors. Buyer, be aware!

Can we trust Gmail?

Gone are the days when E-mails were sent and received from desktops and laptops. Convenience, superior functionality and ease of use drove mass adoption of web based E-mail systems, such as Yahoo, Mail, Gmail, Outlook.com and alike. While benefits of web based E-mail are widely known, very little consideration is given to implications on privacy and security.

Quite often web based E-mail systems claim to be secure based on the fact that the communication between user’s browser and servers is protected by SSL. That is a legitimate claim, but it covers only part of the story and leaves out the big picture.

Let’s say someone sent an E-mail message from their Gmail to dolphin@securedolphin.com. The first leg of communication is indeed protected by SSL and unlikely to be intercepted by 3rd parties. Not so much for the next leg - Gmail needs to locate the server, hosting the mailbox for dophin@securedolphin.com and transmit the message text to that server. And there lies the core of the problem – the transmission is not guaranteed to be encrypted – messages can be hijacked while in transit from one server to another.

It is not unusual for communication between mail servers to be sent in clear text, vulnerable to interception. In a way this is similar to conversation over walkie-talkies – anyone who happens to be listening can possibly hear (or read in case of E-mail messages) the exchange. In case of encrypted E-mail, the unprotected transmission between servers is not an issue, since hijacked messages are scrambled and meaningless unless the interceptor has the secret key, used for encryption.

No matter how secure is the first leg of communication, i.e. the transmission of the message between the device, (desktop or phone) and the web mail provider, the confidentiality of your messages can compromised in transit to the ultimate destination, unless the message is encrypted.

Private messages must be encrypted!

SSL is fundamentally flawed - Google is the latest victim

Google reported another incident of unauthorized issuance of SSL certificates. SSL certificates are used for establishment web of site authenticity. SSL gives users assurances that the site, they are accessing, is indeed the desired web site rather than a fake, created by malicious 3rd parties.

Successful attack on the Indian Controller of Certifying Authorities resulted in unauthorized issuance of certificates for several Google domains. Individuals in possession of fake certificates can mimic Google sites and lure potential victims to give away passwords, credit card numbers and other sensitive information without realizing that sites are not genuine but rather fake.

The fundamental problem with the SSL is that it's security is is based on trust to limited number of commercial organizations (VerySign, Symantec etc.) who are given means to issue certificates to web sites. In theory, these are highly protected, honest and trustworthy organizations. In reality, if history is of any lesson, trusted certificate issuers are as likely to fall victims of an attack as any other organization (Hello Target and mass leakage of credit card numbers. Curious minds are encouraged to check out the Comodo and DigiNotar story also).

NameCoin as oppose to SSL does not rely on trusted issuers for it's names, but rather employes peer-to-peer, decentralized model. The integrity of NameCoin names can't be compromised by attacks against organizations or individuals, involved in NameCoin. There is no single point of failure. The latest Google incident as well as prior attacks on Comodo and DigiNotar are impossible to execute against NameCoin domains.

SecureDolphin relies on NameCoin for secure storage and exchange of cryptographic keys that can be used for encryption of E-mail and other forms of communication as well as secure sign-on with no password transmission over network. SecureDolphin Chrome extension provides easy and convenient tools for E-mail encryption and decryption right in the GMail window.

ProtonMail and PayPal saga - continued

I wrote about the ProtonMail before, in connection with PayPal freezing the account, used for collection of Indie Go Go donations. Checking back some time later, I found that PayPal lifted the gate on the account. When pressed on reasons for freezing the account, PayPal blamed a "human error". The explanation looks fishy to me. But, even if it is true, there still is a fundamental problem, a problem, that I've pointed to before:

Reliance on PayPal, which is subject to regulation and legislative pressure, is the Achilles' heel that drags down ProtonMail

Think of it this way: even if the ProtonMail account was frozen due to human error, the incidents highlights the possibility for PayPal to do that at any time. No, PayPal, being good citizens, likely won't do that voluntarily. Would they have to freeze ProtonMail accounts if summoned to do so? Would they have to comply with requests from FBI, CIA, NSA or other body? I think that is likely. Do I believe in PayPal's best intentions to protect their clientele, i.e. ProtonMail in this case? Absolutely! However, make no mistake, when the question comes to protection of one client vs. loosing the business or affecting hundreds, thousands or million others the choice is likely to be very clear. Is it possible that PayPal finds itself in under treats to be shut down or comply? Yes. Check out the LavaBit story for a recent account of a company being shut down for standing up and backing it's users

I truly hope that ProtonMail learns the lesson and finds ways to eliminate dependencies on centralized services or infrastructure. Going peer-to-peer is the only viable path...Running NameCoin under CentOS and RedHat 6.2

This is a follow-up to the my notes on Compiling NameCoin under CentOS and RedHat 6.2. After the successful compilation, I've tried to start the software and... got a core dump. Running it under debugger quickly revealed the source of problem.

Upon startup, NameCoin daemon attempts to load wallet keys or generate a new wallet if one does not exist (i.e. the wallet.dat file is missing in the data directory, set in the configuration). In either case, it uses OpenSSL to create or load an Elliptic Curve (ECC) key. ECC keys are initialized with certain parameters. Normally, OpenSSL users would use EC_GROUP_new_by_curve_name API call and pass in the unique identifier of the pre-configured parameter set that was shipped with OpenSSL. Apparently, not all OpenSSL distributions are created the same. The version on CentOS and RedHat 6.2 is missing the NID_secp256k1 definition, which results in failure to initialize the key on these platforms.

I've created and submitted a patch, based on ideas and some code from similar patch for BitCoin. However, my patch is still not accepted. Feel free to apply it manually in the mean time.

Obviously, this applies to Fedora also, as I've mentioned in the previous entryProtonMail did not escape the Big Brother!

Building NameCoin under CentOS and RedHat 6.2

- Install required prerequisites yum install boost-static db4-cxx.x86_64 db4-devel.x86_64. boost-static is an umbrella package that brings in all other packages necessary for compiling against boost. NameCoin build instructions ask to download dependency libraries and place in the namecoin/lib directory. With these instructions there is no need to do that.

- Download the source code from GitHub or do git clone https://github.com/namecoin/namecoin.git

- Open the Makefile in namecoin/src directory and remove the -l boost_chrono$(LIBBOOST_SUFFIX) line. There is no libboost_chrono.so or libboost_chrono.a library under CentOS as required code/symbols are included in other boost component libraries

- Go to namecoin/src directory and type make

- Enjoy the result!